- Home

- Marney Rich Keenan

The Snow Killings Page 2

The Snow Killings Read online

Page 2

* * *

I began covering the Oakland County Child Killer case in October 2009 for the Detroit News and continued to research and report on developments in the case for the next 10 years. For this book, I have relied on my own reporting and interviews and extensive research of law enforcement records obtained through the Freedom of Information Act at the federal, state and local levels.

My primary source for the investigation into these crimes has been Det. Cory Williams, through interviews and access to his notes taken over a 15-year span in his role as lead investigator with the Livonia Police Department, and with the Wayne County Prosecutor’s Office, and thereafter from his personal notes as a consultant on the case. I am equally indebted to devoted father and lawyer Barry King for his countless interviews and voluminous record-keeping on the case in the form of numerous memorandums and reports (“Coincidence or Cover-Up”), his D.V.D. film, “Decades of Deceit,” his blog, http://afathersstory-occk.com, his 3,000 pages of records obtained through a very costly Freedom of Information Act request, his many press conferences and public presentations.

Attorney Catherine King Broad, Tim King’s sister, provided her own extensive research and records on the investigation. Her blog on the case, www.catherinebroad.blog, is an unvarnished, fact-filled resource.

For real-time coverage of the abductions, murders and the hunt for the killer, I drew from journalists’ reporting in the Detroit News, the Detroit Free Press, the Royal Oak Tribune and the Oakland Press. Two other media outlets provided insight on the early flourishing of the child pornography and prostitution industries in this country: Marilyn Wright’s incredible reporting in 1976 and 1977 for the Traverse City Record Eagle, and the four-part series, “The Child Predators,” in The Chicago Tribune, with reporting by Michael Sneed and George Bliss, and written by Ray Moseley, published May 15–18, 1977. The New York Times four-part series “Exploited,” published on varying dates from September to December 2019, shed much needed light on present day child pornography, the expertise of criminals who exploit legal loopholes and the complicated psychology of pedophilia.

Tommy McIntrye’s book, Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing, provided an insider’s perspective of the early investigators’ work on the case. I also consulted the book The Fox Islands North and South, Vol. II, by Kathleen Craker Firestone, published by Michigan Islands Research Northport, Michigan (1996). M.F. Cribari’s brave narrative in Portraits in the Snow (2011, Outskirts Press) amply depicted the horror of the pedophile ring in the Cass Corridor during the time of the child killings.

For some specific facts regarding the abductions, murders and autopsies, I referenced the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA) Police Technical Assistance Report, “The Oakland County Special Task Force: Finding the Child-Killer in the Woodward Corridor,” Report Number 77-0340143 dated July, 1977.

1. Bill Laitner, “Study: Oakland County Far Ahead in Michigan for Affluence,” Detroit Free Press, May 18, 2018. https://www.freep.com/story/news/local/michigan/oakland/2018/05/18/university-michigan-economic-study-oakland-county-affluence/621447002/.

2. Gail Leland, “Impact on Victims of Unsolved Murder,” Remarks from Homicide Survivors, Inc., presented to Arizona Cold Case Task Force Report to the Governor and Arizona State Legislature, December 28, 2007.

3. Historical Facts by Decade, Decennial Census of Population and Housing, https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/decade/decennial-facts.1830.

4. Joel Smith, “150 detectives press kidnap search,” The Detroit News, March 23, 1977, 3.

1

“The clock was ticking”

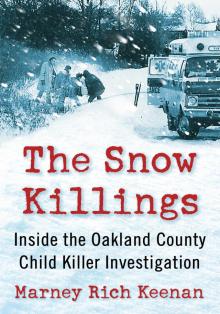

Left to right: Mark Stebbins, Jill Robinson, Kristine Mihelich, and Timothy King, the four victims of the Oakland County Child Killer (Michigan State Police).

Mark Stebbins, Jill Robinson, Kristine Mihelich and Timothy King were all killed by the same malevolent person who came to be known as the Oakland County Child Killer. Their abductions, their torture while in captivity and how they died all fit a wicked pattern—a playbook of depravity and dominance by a murderer that eluded authorities for over four decades.

To fully appreciate how one of the most affluent communities in America was besieged with terror in the late 1970s, the story must begin a full month before the first victim of the Oakland County Child Killer was snatched.

At around 8:30 in the evening on January 15, 1976, Cynthia Cadieux, a 16-year-old student at Roseville High School, left a girlfriend’s house to make the 10-minute walk to her home in Roseville, a small working-class community of 10 square miles, northeast of Detroit in Macomb County.

Described as a tall, pretty, blue-eyed brunette, Cynthia never made it home that night.1 Five and a half hours later, a motorist traveling 15 miles west of her home slammed on his brakes. Cynthia’s nude and badly beaten body lay in the middle of Franklin Road, in neighboring Oakland County. At some point during her hellish journey across the county line, she had been raped and sodomized, her skull crushed by a blunt instrument.

Her mother, Wanda Nelem, said she and Cynthia’s stepfather did not expect her home that Thursday night; they thought she was going to stay with her friend and attend school with her in the morning. Thus, they were unaware of anything unusual until Friday afternoon when Cynthia didn’t come home from school. By 6:30 p.m. Friday night, the couple was filling out a missing person’s report. Hours later, as a Roseville police officer was driving to Nelem’s home to notify them of Cynthia’s death, the couple learned on the 11 o’clock news that a girl’s body had been found on Franklin Road by a passing motorist.2

Four days later, an intruder was unleashing mayhem on an otherwise quiet residential street in Birmingham. Over the course of 45 minutes, beginning at 8 p.m., a man broke into three homes on Villa Street using a crowbar and screwdriver. He tied up homeowners, tore through rooms stealing jewelry and cash, then moved on to the next house. By the time he entered the back sunroom of the home where 14-year-old Sheila Srock was babysitting, he had decided to up the ante.

A freshman at Marian High School, an all-girls Catholic school, Sheila lived with her older brother, James H. Srock, on nearby Lincoln Avenue—their parents had recently died from cancer. An excellent student, Sheila played the piano and had spent the last day of her life ice skating with a good friend.3 The intruder raped and sodomized her, then shot her five times in the stomach with a .38 caliber handgun. As Sheila lay dead on the floor, slumped against a giant Snoopy stuffed animal, the robber-turned-killer calmly departed, mingling with a small crowd that had gathered outside upon hearing the shots. He quietly slipped into his gold, two-door 1967 Cadillac and drove off into the night.

Weeks passed. The killers of Cynthia Cadieux and Sheila Srock were not apprehended, and police were not reporting any solid leads. Then, another child vanished, this time in broad daylight.

After lunch on Sunday, February 15, 1976, Mark Douglas Stebbins, 12, decided to walk home from the American Legion Hall in Ferndale, a working-class neighborhood just south of Birmingham and Franklin. Mark had gone to the hall with his older brother, Michael, 15, to watch a pool tournament. The boys’ mother, Ruth Stebbins, worked as a bartender there.

Mark was bored with the pool game and wanted to go home to watch the World War II movie Destination Tokyo starring Cary Grant on TV. He said goodbye to his mom and Mike and left at around 1:15 p.m. for the three-quarter mile walk home.

He never made it. That evening around 11 p.m., Ruth Stebbins, who was divorced from Mark and Mike’s father, reported her boy missing.

Just under five feet, Mark had strawberry blond hair and blue eyes. Ruth told the police dispatcher Mark was wearing a blue hooded parka, a maroon sweatshirt, Levi’s jeans, and black rubber boots. A shy, sweet seventh grader at Lincoln Junior High School, he loved baseball and fishing. He dreamed one day of becoming a Marine. Now, Mark had dropped off the face of the earth.

&n

bsp; After a thorough search, Ferndale police told newspaper reporters they were not able to locate anyone who had seen Mark walking home, much less being abducted. They had even contacted the Shrine Circus—it had left Detroit Sunday night for a show in South Carolina—on the off chance he might have run away to join the circus.

“This is not a routine missing person case and we are quite concerned,” Ferndale Police Chief Donald Geary said. “He had no money or wallet on him.”4

When police requested a photo of Mark to put on a “missing” poster, Ruth Stebbins said she had been struggling financially and hadn’t had enough money to pay for school photos. She described Mark and his clothing—a blue parka with a fur-lined hood, a maroon sweatshirt and blue Levi’s jeans—to a police sketch artist who constructed a composite drawing. By Tuesday, the sketch and a description of Mark would be distributed in 5,000 flyers throughout Oakland County.

On Thursday, February 19, four days after Mark vanished, businessman Mark Boetigheimer left his office at the Fairfax Plaza complex in Southfield—about four miles from where Mark disappeared—at about 11:30 a.m. and headed to the nearby drugstore at the New Orleans strip mall. At the northeast corner of the parking lot, he spotted a figure lying against a four-foot red brick wall separating the office plaza parking lot from the lot next to the strip mall. At first, Boetigheimer thought it was a mannequin. As he came closer, he saw the body of a young boy. Mark was wearing the same clothes he had worn when he disappeared, lying face up, his hands folded over his chest, his head cradled in the fur-lined hood. Boetigheimer hurried back to his office and called police.

Within hours of the discovery, Southfield police interviewed another occupant of the office complex. Mack M. Gallop had walked his Schnauzer along the edge of the parking lot at around 9:30 that morning. He said he was certain the dog, who was on a 20-foot leash, would have picked up the scent had the body been there. Police concluded the drop-off had to have been done after 9:30 a.m.

The autopsy, performed by Oakland County Deputy Medical Examiner Dr. Thomas J. Petinga, determined that the cause of death was asphyxia—Mark was suffocated. His wrists and legs bore discoloration and marks indicating he had been bound. There were two small, crusted lacerations on his left rear scalp and blood stains had been found on the hooded portion of his jacket. Evidence showed that Mark had been repeatedly sodomized but there was no trace of semen on his body or on his underwear.

Southfield and Ferndale police detectives immediately began working around the clock on the case. On Sunday, February 22, Ferndale officers stopped passing cars in the area near the American Legion Hall in an effort to find someone who had seen Mark walking home. The Detroit News administered a $5,000 reward to be offered through a “Secret Witness”5 program. (That amount would grow exponentially as more kids were snatched.) The public was encouraged to anonymously phone or write in any information they might have on the case. Tips were sent to a P.O. box administered by the police. Instead of providing their names, tipsters would assign to their tips a six-digit number they generated themselves. Using that number, police would then post notices in the paper if they wanted additional information from the tipster. Scores of tips came in, but none of any value.

Mark’s father, Lester A. Stebbins, 47, flew in from Houston for his son’s funeral. Lester and Ruth had divorced in November 1968. Perhaps because the cops had few if any leads, they jumped on the grieving father. Fresh off a plane at Detroit Metropolitan Airport and accompanied by his then wife, Margaret, Lester Stebbins was arrested by Oakland County authorities and charged for being $24,600 in arrears on child support payments, a felony carrying a maximum sentence of three years in prison if convicted. Lester Stebbins was allowed to visit the funeral home but spent the night at Oakland County jail.

Released Sunday afternoon, Stebbins was allowed to attend his son’s funeral on Monday at St. James Catholic Church. Immediately following graveside services at the cemetery, he was rearrested. An attorney representing Stebbins described him as a man “with a lot of personal problems who was very upset and heartbroken” about his son’s death. “The purpose of the prosecutor’s office’s action is to punish him,” the attorney said. “And if they prevail the result would be imprisonment which wouldn’t improve the situation at all.”6

A day after the funeral, someone placed a memorial/prayer card from Mark’s service in the parking lot where the body had been discovered. Initially, this was investigated in keeping with the long-standing theory that a murderer always returns to the scene. Later, it was determined a mourner had likely left it there.

Police did have one suspect. On March 16, 1976, close to 6 p.m., a 54-year-old convicted sex offender kidnapped a seven-year-old boy who was walking home with his friend in Madison Heights, a neighborhood right next to Ferndale. James Joseph Crafton, whose prior convictions involved sex offenses against young girls, pulled up alongside the two boys and said, “Come on, I’ll take you home. I’m a policeman.” The victim’s seven-year-old friend, Michael Justice, told his friend not to get inside the car. Justice told a reporter: “He didn’t look like a cop to me, but he climbed in the front seat and the man closed the door real quick and drove away fast.” Crafton disappeared with the boy. Three hours later, he dropped him off back home after sodomizing him.7 After his arraignment the following day, Crafton was given a polygraph by Ferndale detectives in the slaying of Mark Stebbins. According to MSP records, his tip sheet indicates he passed.

Six months went by. On August 7, 1976, Jane Louise Allan, 14, hitchhiked from her Royal Oak home to see her boyfriend in Auburn Heights, a distance of about 17 miles. She left sometime after 12:30 p.m. According to police reports, once she arrived, she and her boyfriend had a disagreement and she left, presumably to catch a ride home. She was last seen walking with her thumb out near I-75 and University Drive in Pontiac.

Four days later, Jane’s body was found floating in the Great Miami River in Miamisburg, Ohio. Her hands had been tied behind her back with shreds of a t-shirt. The Ohio coroner’s office believed she was dead before she was tossed in the river, possibly from carbon monoxide poisoning, believed to be caused by riding in the trunk of a car after being abducted. Decomposition made it impossible to tell whether she had been sexually molested.

Come winter that year, a killer was on the prowl again, marking the fourth child’s disappearance and death to rattle the community’s sense of security.

Jill Robinson, 12, was upset about something on the evening of Wednesday, December 22, but refused to talk about it. Her mother, Karol Robinson, had been making dinner. The single mother, who worked as a court reporting teacher, had asked Jill to make biscuits, but Jill refused, walking out the door in a huff. The story that ran in the papers was that Karol and Jill had an argument and Jill had run away. That misrepresentation pained Karol Robinson deeply for decades to come.

Jill lived in Royal Oak with her mother and two younger sisters, Alene, nine, and Heather, six. Karol and Jill’s father, Tom Robinson, separated in 1972; they had been divorced a little over a year. The girls spent Wednesday nights and weekends with Tom, an English professor at Oakland Community College, who lived in nearby Birmingham. But on this Wednesday night, for reasons no one can now remember, the girls were not going to their father’s house. Perhaps that was what set Jill off—she was especially close to her father—but no one knows for sure.

Karol had confided in Ted Rodinsky, a self-described private detective who was dating Karol at the time, that Jill had been especially moody and quiet lately. Rodinsky had advised Karol she should diffuse the tensions between her and Jill by telling her to go outside and think about her behavior. At the time, Karol says she rejected that approach. “I said I can’t tell her to go outside; that’s the craziest thing I ever heard.”8

Navigating the crossroads of adolescence, her parents’ divorce, moving to a new home, starting a new school, making friends, and missing her dad had been

hard on Jill. She had even become preoccupied with the notion she was going to be killed. “A few months before she died, I was talking with her in her bed, saying her prayers with her,” Karol remembered. “She had tears in her eyes and I said, ‘Oh, honey what’s wrong?’ She was very fearful. She said she felt someone was going to shoot her. She said, ‘I know it’s a crazy thought, because who is going to do this to a little girl? But I’m really worried this is going to happen.’”

Karol arranged for Jill to see a child psychiatrist. The psychiatrist said Jill was fine and suggested getting Jill a cat she had wanted. “Fluffy” soon became part of the family.

A sixth grader at Longfellow School, Jill had fair skin and a spray of freckles under her soft brown eyes, was an excellent, almost “all A” student who enjoyed English, social studies, and science. Karol said she almost always had her nose in a book. She even read the newspaper. “She was a young girl,” Karol said. “But she was very emotionally mature for her age.”

Jill had been looking forward to Christmas. With her allowance, she had already bought and wrapped Christmas presents for her sisters—a stuffed animal for Alene, and for Heather, a Barbie hair dryer. Just weeks earlier, for her twelfth birthday on December 2nd, Jill had 12 girls at her house for a party. Jill also loved to bake with her mother in the kitchen, so the biscuits were not an unusual request.

On this early evening, Karol wanted to get dinner on the table in time for her to attend church services afterwards. But Jill was “stomping around” the house, visibly upset about something. Karol begged Jill to talk to her—had anything happened at school? A fall-out with friends? Jill refused to answer.

The Snow Killings

The Snow Killings