- Home

- Marney Rich Keenan

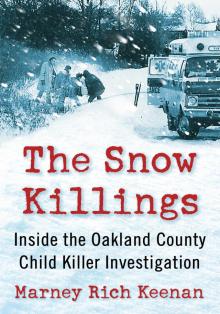

The Snow Killings Page 8

The Snow Killings Read online

Page 8

The Tribune investigation estimated the number of kids involved ran as high as 100,000. Most were runaways but some were kids sold into prostitution and/or pornography by their parents. The reporters found pornographers in at least five states had used government funds to establish foster homes for their prostitution and pornography operations. In Mineola, New York, a film ring was broken up that included policemen who had been filmed having sex with their daughters. Los Angeles police found a three-year-old girl, a five-year-old girl and a 10-year-old boy whose mothers had sold them into pornography.

It wasn’t until the summer of 1976 that the first thread of the nationwide child pornography ring started to unravel. It began in Michigan, with the arrest of a gym teacher at a Catholic school in St. Clair County who had connections to the OCCK case.

Gerald Richards, a 29-year-old physical education teacher at St Joseph’s Elementary in Port Huron (60 miles from Detroit), was arrested for raping a 10-year-old boy in July 1976. Richards, a married father of two, was supplementing his teaching salary producing and selling child pornography. As part of a plea agreement, Richards led police to Grosse Pointe real estate developer Francis D. Shelden, who had purchased North Fox Island in Lake Michigan, where he made films for a worldwide child pornography ring.

A search of Richards’ home unearthed still photographs, 8mm films, and lengthy client lists with their addresses. The evidence prompted Michigan State Police to alert authorities all over the country about children at risk in their jurisdictions.

In a matter of weeks, law enforcement shut down rings across the country. In New Orleans, police raided the headquarters of a Boy Scout troop and arrested the scout leader for involving more than 30 young boys, mostly wards of the state, in prostitution and pornography. Police in Dallas seized a mailing list of more than 30,000 clients from a convicted pedophile. And, in Tennessee, the Rev. Claudius I. “Bud” Vermilye, purporting to be an Episcopal priest, was arrested for running “Boys Farm,” a child porn operation billed as a private rehabilitative home for teenage boys.

Within weeks of the Tribune series’ publication, two dozen U.S. senators on the Committee on the Judiciary convened to address “a new menace to youth that has mushroomed into big business in America: the exploitation of young boys and girls for the purpose of producing pornography.” Among other social failures like poverty and unemployment, the senators blamed the breakdown of “family values,” specifically: “the lack of responsibility being demonstrated by American parents in their marriage relationships.”6

Sen. John C. Culver of Iowa noted: “Incredibly there is at the present time no federal law which is directed at this form of child abuse. … The challenge that faces us is not simply one of physical protection. Its nuances are infinitely more subtle and complex, and the problem cuts across social strata, all economic and regional groups.”

Sen. Malcolm Wallop of Wyoming blamed the judicial system: “The courts are ever too lenient and ever too ready to grant the protective shield of the Constitution to those who prey and not to their victims. The courts bear a heavy burden of guilt and face the immediate task of reversing this dismal course. … I just cannot believe that those who would abuse [children] and use the products of that abuse for profit can be in any way able to claim the protection of the First Amendment.”7

After two days of hearings in May 1977—during which Gerald Richards gave testimony—the senators began drafting legislation culminating in the November passage of the Protection of Children Against Sexual Exploitation Act. The law made child pornography a federal offense and imposed for violations a fine of $10,000 and/or imprisonment up to 10 years.

Sadly, the public outrage and legislation was too little, too late for the victims of the Oakland County Child Killer. To be sure, the automotive capital of the world in the early seventies was fertile ground for the child porn industry and sexual traffickers. The 1973 oil crisis wrought a dramatic drop in car sales. As gas prices skyrocketed, consumers turned to smaller fuel-efficient Japanese and German imports instead of Detroit’s high-performance muscle cars and behemoth station wagons. Layoffs hit the Detroit auto industry hard. Still grappling with the aftershocks of the 1967 racial riots, the city of Detroit racked up 714 homicides in 1974. The Motor City was now dubbed the nation’s “Murder Capital.”8

Hardest hit in the recession was a 10-block area northwest of Detroit called the Cass Corridor. Once a thriving, dense neighborhood filled with poor families from the South who had migrated north for work in the auto factories, the area was devastated by the tsunami of economic recession. Intact families living on top of each other in apartment buildings broke up, leaving behind single parents and lost, wayward kids. Soon, the sex trades found their new home. Pimps, prostitutes, johns and dope dealers populated dive bars and seedy hotel rooms. Scrappy kids ran free—the area became a predator’s utopia. One pedophile who owned a bike shop in the heart of the Cass Corridor set up a child porn photo studio in the basement of his home. Another porn operation ran out of a church basement.

While the porn ring was in full manic swing, just across Eminem’s infamous Eight Mile Road—long considered the line of demarcation between the inner-city slums and the affluent suburbs—the Oakland County Child Killer was trolling for prey. As one victim of Cass Corridor rings would tell an investigator some three decades after the OCCK crimes had gone cold: “Kids disappeared from here all the time back then, but nobody cared until those Oakland County kids went missing.”9

Nobody did more to cement that divide than Coleman Young, mayor of Detroit from 1974 to 1994. In one of its retrospective issues, Time magazine said of Young: “Suburbanization turned Detroit into a majority-African-American city, and its first black mayor spent his twenty-year tenure playing the politics of retribution, sending thousands of white Detroiters to the suburbs. The exodus institutionalized racial divisions that have only hardened ever since.”10

Suffice it to say, the openly hostile mayor who christened an entire class of people as “those racists in the suburbs” and sanctioned the 1967 riots as “a rebellion” had virtually no admirers in Oakland County.11

The second-most populous county in the state of Michigan, Oakland County has long been ranked as one of the top 10 most affluent counties in the nation. Its once pristine 900 square miles, located directly north of the city, were once the premiere site for summer homes and country estates belonging to auto barons and wealthy entrepreneurs. In the mid-seventies, Oakland County’s population soared to one million residents. Families were attracted to the desirable neighborhoods, nationally ranked schools and thriving arts and cultural centers.

To the south, the county boasts the historic Detroit Zoo; one of the nation’s oldest and largest, it consistently ranks among the top 20 best zoos in the country. To the north is the Cranbrook Educational Community, one of the world’s leading centers of education, science and art, situated on a 300-acre campus critics have called “the most enchanted and enchanting setting in America.”12 In 1969, the Somerset Collection, an upscale, luxury shopping mall opened to wide acclaim. With Sax Fifth Ave. and Tiffany’s among its flagship offerings, the Collection remains one of the most profitable malls in the country.

And yet, for all its manicured lawns, preeminent schools and prized family values, Oakland County—so named for its prevalence of oak trees—would become forever tainted with the moniker of a sadistic child predator. As one reporter for the Detroit News wrote during the height of the killings: “And to think some people flee Detroit for the safety of Oakland County.”13

* * *

1. Richard Kopeikin, states attorney investigator in “Child’s Garden of Perversity” (no author listed), Time magazine, April, 4, 1977.

2. Michael Sneed and George Bliss, “Child Pornography: Sickness for Sale”: Chicago Tribune, May 15, 1977, 1A.

3. Charlie Lentz, “Sandusky: Second to None,” http://pennstate

.scout.com/2/630302.html, March 27, 2007.

4. Dan Mangan, “Girls Who Appeared to Be 11 to 12 Seen with Jeffrey Epstein Getting Off His Plane in 2018 as Authorities Eyed His Travel Abroad,” https://www.cnbc.com/2019/09/11/jeffrey-epstein-seen-with-young-girls-getting-off-his-plane-in-2018.html, September 12, 2019.

5. Sneed and Bliss, “Child,” 20.

6. U.S. Sen. John C. Culver, Iowa, Opening Statement in “Protection of Children Against Sexual Exploitation” Hearings before the Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency, Judiciary Committee of the United Senates Senate. May 27, 1977, 1.

7. Culver, Senate Hearings. 2.

8. Stephen Franklin, “Murders Torment Detroit,” Chicago Tribune, January 13, 1987.

9. John Thompson to Det. Sgt. Cory Williams in interview, January 3, 2006.

10. Photo caption: “How Detroit Lost Its Way” Time, September 24, 2009.

11. “About Cranbrook” https://www.cranbrook.edu/about.

12. Patrick Mallon: “Detroit: Coleman Young’s Triumph of Self-Destruction,” www.freerepublic.com, April 8, 2002.

13. Joel J. Smith, “Killed or Missing: Five Children,” The Detroit News, January 7, 1977, 1B.

4

The Snow Killings

1977: Berkley, Michigan—The kitchen phone rang as the boys were clearing the Sunday dinner dishes. Det. James “Lee” Williams, his wife, Lucy, and their sons—Mark, 23, and twins Cody and Cory, 15—were preparing, albeit reluctantly, to return to work and school after the New Year’s break.

They hoped that getting back into life’s routine would quell the anxiety behind the facade of holiday cheer. Three days before Christmas, 12-year-old Jill Robinson from nearby Royal Oak had jumped on her bike and pedaled off into the night. Christmas came and went. Then, at 8:45 a.m. on December 26, passersby saw something on the shoulder of the northbound I-75, close to the Sixteen Mile Road exit. It was Jill’s fully clothed body. She had been shot in the face.

Only 10 months earlier, Mark Stebbins of nearby Ferndale had been plucked off the sidewalk while walking home. Like Jill, Mark had been missing for several days before he was found dead. Little trace evidence had been left behind at the crime scenes. Everyone was on edge. Neighbors were not accustomed to eyeing each other warily down the Formica counter at the coffee shop. It was not normal to double check the back seat in the station wagon, or to corral the kids indoors long before dark fell. But the madness had been rolling in like a fog. Soon, it would be all encompassing.

Young Cory answered the phone and an impatient man asked for his father. Lee Williams took the phone begrudgingly. He worked the phones for a living. Did he really have to make nice on the phone during off hours? He had retired two years earlier as a Detective Sergeant for the Berkley police department. Now, he was working for Oakland County Prosecutor L. Brooks Patterson as an investigator.

Berkley Police Det. Lee Williams in the fifties (courtesy of the Williams family).

It was Bob Bell on the other line. Bell was an old friend; the two grew up together in Royal Oak during the lean years of the Great Depression. They had both served in World War II and had come back to settle down in Berkley to raise their families. Occasionally, they would get together with their wives for dinner, maybe a movie. They mused about possibly retiring down south.

But now any prospect for their carefree golden years was about to be shattered. Lee knew it the minute Bell said his granddaughter’s name.

“It’s Kristine!” Bell yelled, his words coming in a breathless stream. “We can’t find her anywhere! Debbie is out of her mind. Jesus Christ, Lee, you gotta help us.”

“Calm down,” Lee said. “Slow down, Bob. Tell me what’s goin’ on. From the beginning.”

Five hours earlier, Bell’s 10-year-old granddaughter, Kristine Mihelich, had left home to walk a few blocks to the 7-Eleven. Bell’s daughter Debbie worked across the street from the 7-Eleven at Hartfield’s Bowling Alley, so it was not an unusual trek for Kristine. But she never returned home. By 6 p.m., Debbie had canvassed the neighborhood and phoned all of Kristine’s friends. Then she’d called the police.

Cory Williams overheard his father’s muffled tones. He and his brother were sophomores at Berkley High School. Never had they feared for their own safety. They rode their bikes everywhere—to the movies, to the baseball diamond, to kill time in between adventures. Lucy Williams had one rule for her boys: “Be home before the streetlights come on.” It was a rule she rarely had to enforce.

Lee yanked on the twisted phone cord as he ducked behind a door, trying to calm his frantic friend without alarming his family. All Cory knew was that his father was asking a lot of questions. But later that night, Lucy came into the twin’s bedroom. She spoke to her boys in measured tones: Kristine had gone missing.

Cory Williams had seen the “MISSING” posters of Mark Stebbins tacked on telephone poles in his neighborhood. Now Kristine had likely been kidnapped while at the same 7-Eleven where he and his brothers bought Slurpees and did wheelies on their bikes in the parking lot.

For the first time in his young life, Cory felt real fear. “It was starting to sink in that it could have easily been one of us,” he recalled.

Many Oakland County residents posted “white hand” flyers in the front windows of their homes as a sign of a safe house kids could run to if they felt threatened (author scan).

Concerned residents could post a flyer depicting a “white hand” in the window of their homes as a sign of a safe house children could go to if they felt they were being pursued or were suddenly uncomfortable outside. “We were told to look for the hand in the window and head for that house,” Williams said. “I remember seeing these homes with the white hand sign in our neighborhood and it worried me as a kid. I kept thinking what if the killer was chasing me and the people with their hand in their window had their door locked or weren’t home. My brothers and I would lie in bed and talk at night about how scary all of this was and what we would do to get away from the killers if we had to.”

Lee Williams worked the case like mad, both on the job and on his own time, for his good friend, for all his friends, for his own family. Police launched a massive effort, scouring the area, knocking on doors and taking statements from residents and merchants alike. Volunteers organized search parties, methodically canvassing brush and woods. CB radio aficionados cruised in their vehicles nightly, speedometers barely registering, shining flashlights in empty storefronts. Tips poured in. None of it was of any use. Kristine would be missing an agonizing 19 days. Cory Williams would never forget those 19 days, nor the toll it took on his father.

In 1979, one year after the Task Force shut down, Cory Williams graduated from Berkley High School, Class of 1979. He began his career in law enforcement after seeing an advertisement in the paper that said the Livonia Police Department would pay college tuition while he worked as a police cadet. Livonia was a large middle-class suburb of Detroit with an array of traditional neighborhoods built in the fifties, located in northwest Wayne County.

After testing and interviews for Livonia PD, Williams was hired along with 11 other cadets. He booked prisoners in the jail during the day and attended classes at the local community college at night. But two years later, the economy went south and Williams was laid off, along with nine other cadets.

With the aim to follow in his father’s footsteps diverted, Williams decided he would become a U.S. Paratrooper like Wes Williams, his uncle. Lee Williams, along with both his brothers, were part of the Greatest Generation warriors fighting in World War II. Young Cory had always been enthralled with his Uncle Wes’ stories of parachuting into Normandy with the 82nd Airborne during the D-Day invasion. So, in the summer of 1983, Cory Williams walked into a military recruiting office and joined the Army.

One month before he was scheduled to ship off to basic

training at Fort Benning, Livonia Police called him back to work. But Williams was already committed to the military; he’d already been sworn in. “I’ll see you in three years,” he told them.

After graduating from basic training and infantry school at Fort Benning, Williams entered the Army Jump School. As a U.S. paratrooper stationed at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, Williams was proud to have earned assignment to the same unit his uncle had: the 82nd Airborne Division, 2nd Battalion of the 325th Airborne Infantry Regiment, known as “The White Falcons.”

Cory Williams in 1984 at infantry training for the U.S. Army’s 82nd Airborne Division at Fort McCoy, La Crosse, Wisconsin (courtesy Williams family).

Williams earned top honors at the Army Sniper School. Out of 40 snipers that competed for the U.S. Paratroopers team nicknamed “The Jumpin’ Junkies,” Williams placed among the top 10. For the next three years, he would train snipers in the mountains of Tennessee and North Carolina and became one of the co-authors of the Army Sniper Training Program at Fort Bragg.

In 1985, Williams came home and was excited about finally becoming a police officer. His two brothers were now working as cops, which meant that all four of the Williams men were on the job in law enforcement in metro Detroit. Lee Williams was never prouder; Lucy Williams was never more worried.

As a young, aggressive patrol officer working in Livonia in the late eighties, Williams was unabashedly trying to make a name for himself. Averaging 40 arrests a month, it was not unusual for Williams to be involved in as many as two to three police pursuits a week for armed robberies, car thefts, and break-ins. At the end of one month, his shift had totaled close to 400 arrests, a record that led to the FBI naming Livonia one of the top safest cities in America.

The Snow Killings

The Snow Killings